Transgressing the disciplinary boundaries: Ernst Mach

17.06.2020

Ernst Mach (1838-1916) has been one of the most prominent, multifaceted intellectuals at the turn of the twentieth century. Educated as a physicist and mathematician at the University of Vienna, Mach largely transgressed these disciplinary boundaries, leaving a deep mark, besides in physics, in fields such as history and philosophy of science, physiology, and psychology [3]. Mach is vastly known among physicists for his work on sound waves (he was the first to experimentally demonstrate the Doppler effect) and for being among the foremost inspirations in the development of Einstein’s theory of relativity (as acknowledged by Einstein himself), as well as for being the main adversary of Ludwig Boltzmann in the debate about the reality of atoms (the latter narrative has however recently been much scaled down by historians, see [3,4]). Moreover, despite he called himself a “holiday sportsman” (“Sonntagsjäger”) in philosophy, Mach has in fact been one the leading figures of the Viennese philosophical landscape, being a prime influence on the intellectual program of the Vienna Circle. Indeed, Mach was appointed what could be regarded as the first chair worldwide in history and philosophy of science, “in particular the history and theory of inductive sciences”, which was specifically created for him at the University of Vienna in 1895 [3]. After Mach’s retirement, that chair was partly to be occupied by Boltzmann and, later on, by the founder of the Vienna circle, Moritz Schlick.

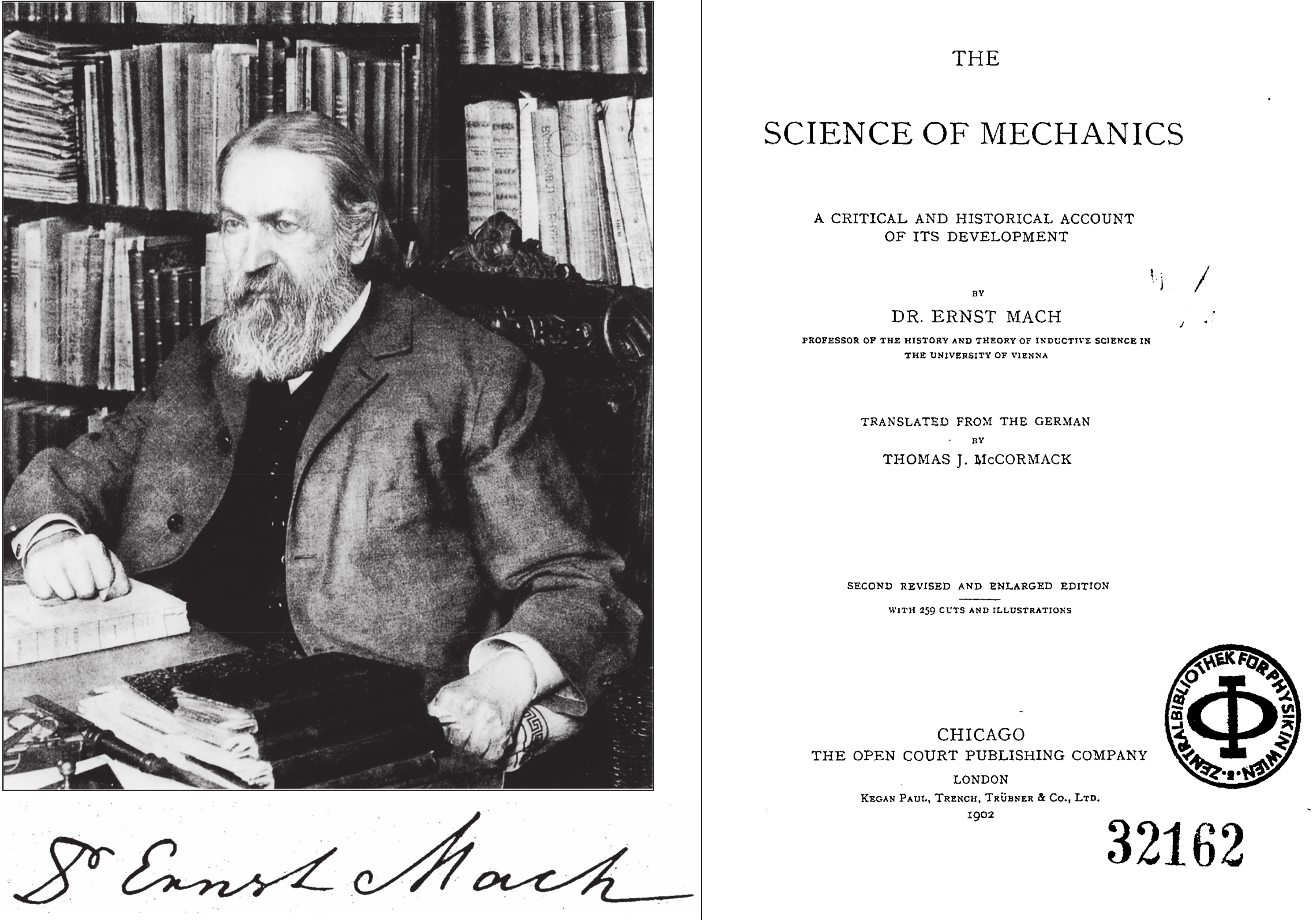

As for his interdisciplinary interests, Mach had already read Kant at the age of 15, and –as he would later recall in his autobiographical notes– this “made a powerful impression upon him, destroyed the young man’s naïve realism, stimulated an interest in epistemology, and with the help of Kant the metaphysician annihilated all tendency toward metaphysics within himself.” [3]. The philosophy of Mach is, in fact, characterised by an anti-metaphysical attitude (strongly advocating empirical evidence which became the most central element in the epistemological approach of the Vienna Circle), together with an anti-realist stance (e.g., against the existence of atoms as substances). This attitude was inspired by Mach’s lifelong scepticism towards any traditional metaphysical philosophy as producing pseudo-problems. Moreover, Mach’s philosophy had a clear empiricist approach, according to which “sensations” in form of complex elements are the only given and science should aim at merely describing observable phenomena in the most economical way [5]. Worth mentioning is also Mach’s critical-historical approach aimed at the elucidation of present physics through historical analysis, which identifies him as a forerunner of the modern discipline of “History and Philosophy of Science” and historical epistemology (see his influential book “The science of mechanics: A critical and historical account of its development”, in the figure).

Mach has been one of the central figures of intellectual life at the turn of the century and, especially in Vienna, his influence on modern physics was deep and long-lasting even when this is far from being evident. For instance, despite the usual narrative that portraits Schrödinger as a strong realist and anti-positivist, he was actually profoundly influenced by Mach’s philosophical views [3, 6]. In this respect, Einstein’s words reminding us of Mach’s historical relevance seem still today about right: “I even believe that the people who consider themselves opponents of Mach, scarcely know how much of Mach’s way of thinking they have absorbed, so to say, with their mother’s milk.” [3].

References

[1] Source: Österreichische Zentralbibliothek für Physik, original link: https://phaidra.univie.ac.at/o:740462

[2] Source: Österreichische Zentralbibliothek für Physik, original link: https://phaidra.univie.ac.at/o:699263

[3] Stadler, F., 2019. Only a Philosophical “Holiday Sportsman”?–Ernst Mach as a Scientist Transgressing the Disciplinary Boundaries. In Stadler (ed.), Ernst Mach–Life, Work, Influence (pp. 3-21). Springer, Cham.

[4] Blackmore, J.T., Itagaki, R., Tanaka, S. and Tanaka, S. eds., 2001. Ernst Mach's Vienna 1895-1930: or phenomenalism as philosophy of science (Vol. 218). Springer Science & Business Media.

[5] Pojman, P., "Ernst Mach", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2019/entries/ernst-mach/; Erik C. Banks, 2014. The Realistic Empiricism of Mach, James, and Russell. Neutral Monism Reconceived Oxford University Press.

[6] de Regt, H. W., 2001. Chapter Erwin Schrödinger in Ref [4] (pp. 84-104).

Further resources

Working group on History of the Philosophy of Science also dealing with the life and work of Ernst Mach, Commission for History and Philosophy of Sciences of the ÖAW: https://www.oeaw.ac.at/kgpw/

Stadler F., together with Heidelberger M., Hoffmann, D., Nemeth, E., Reiter, W. Renn, J., Wolters, G. 2008-2020. Ernst Mach Studienausgabe (Project for the publication of nearly the entire work of Ernst Mach as a study edition):

https://www.xenomoi.de/philosophie/mach-ernst/216/ernst-mach-studienausgabe